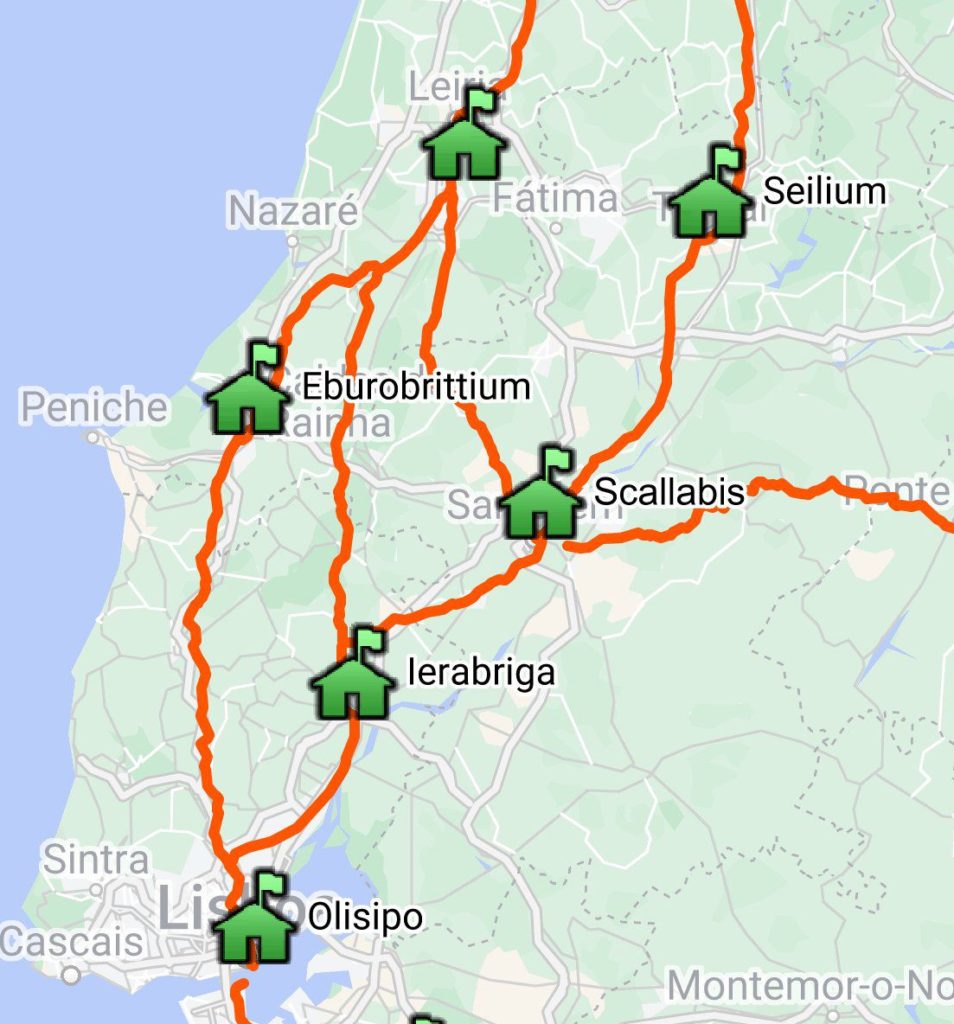

Continuando a série de posts sobre o Itinerário XVI vamos agora analisar a sua passagem por Santarém rumo a Tomar. Não restam muitas dúvidas sobre a associação do povoado que ocupava o morro de Santarém a Scallabis. Segundo o Itinerário, esta estação estava a 32 milhas de Ierabriga, distância compatível com o percurso entre o Povoado dos Castelinhos e a base do morro de Santarém junto à margem direita do Tejo (ver post anterior).

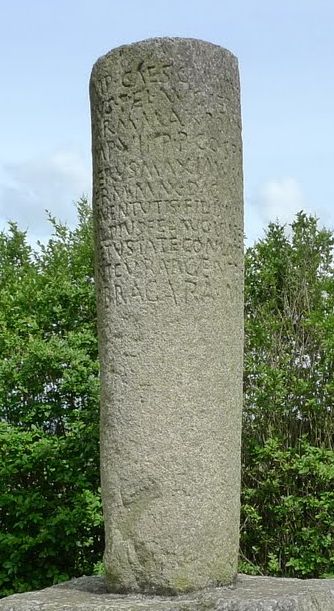

Item ab OLISIPONE BRACARAM AUGUSTAM m.p. CCXLIII

Ierabriga m.p. XXX

Scallabis m.p. XXXII

Seilium m.p. XXXII

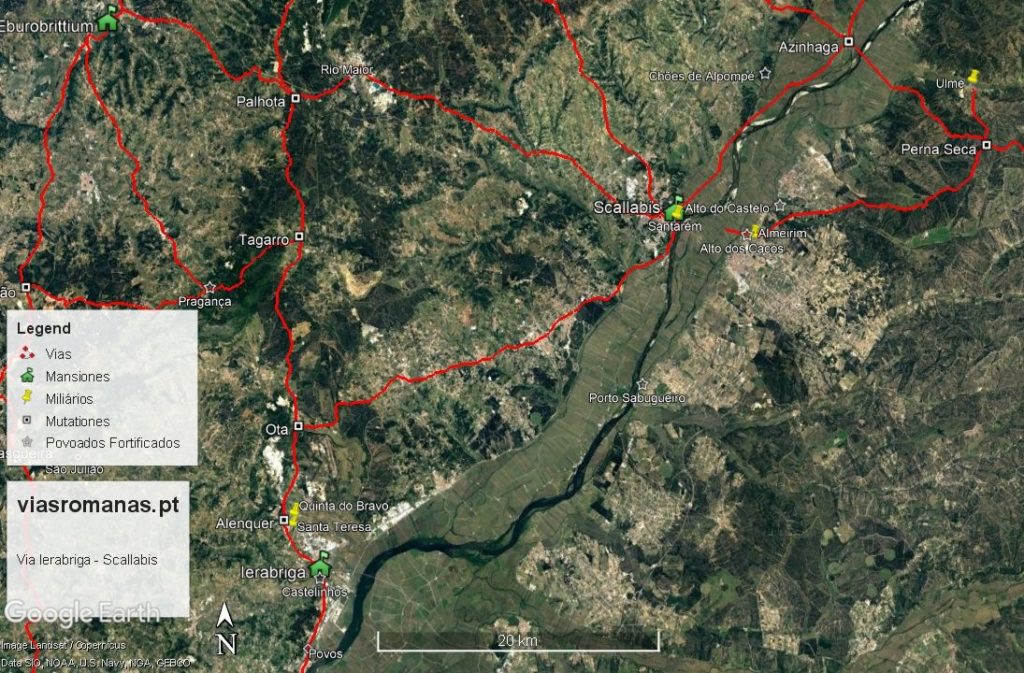

De Scallabis a via continuava até Seilium percorrendo, segundo o Itinerário, 32 milhas. Ora, este valor parece insuficiente para cobrir o percurso entre Santarém e Tomar dado que a distância em linha recta se aproxima já das 31 milhas. Deste modo, é provável que a via seguisse pela margem do rio e não uma rota mais interior passando por Torres Novas como tem sido proposto (Mantas, 1996; Romão, 2012). Aliás, este corresponde ao trajecto descrito pelo Padre Castro no seu Roteiro Terrestre para a Estrada Real de Santarém a Tomar.

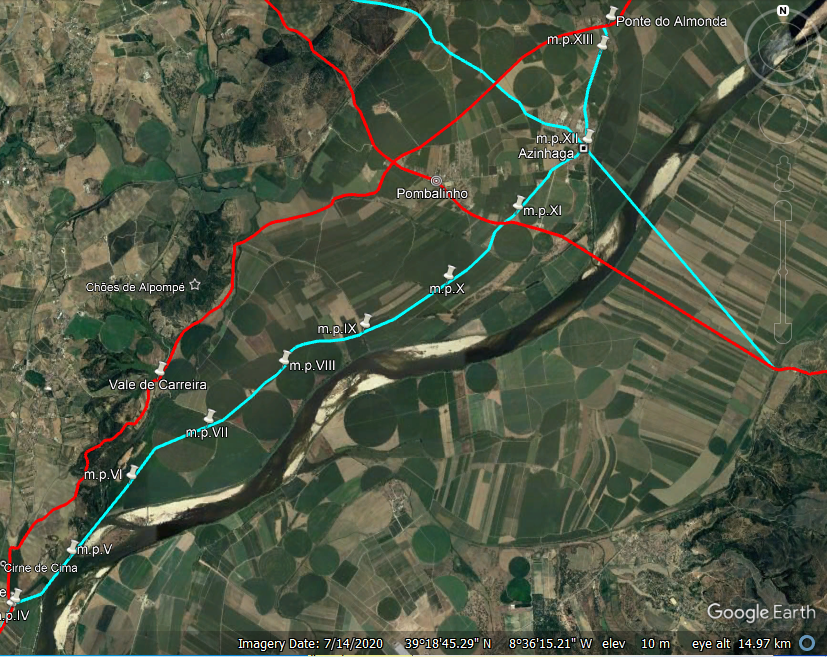

A partir de Santarém a via seguia por quatro milhas (uma légua) até à “Cruz da Entrada”, também designada por Cruz da Légua , havendo vestígios romanos nas proximidades (Cirne). Logo depois fazia a travessia o rio Alviela para daí cruzar a antiga Ilha de Alvisquer por Azinhaga rumo à Golegã (Figura 2). Inicialmente fizemos passar a via próximo do importante povoado fortificado de Chões de Alpompé (a 8 milhas a norte de Santarém) e do povoado de Pombalinho (vestígios de ocupação que remonta à Idade do Bronze).

No entanto, a marcação miliária aponta para um traçado mais recto seguindo em direcção a Azinhaga, a 12 milhas a Santarém, sugerindo que neste local haveria estação viária, provavelmente uma mutatio. Aliás, o topónimo Azinhaga remete para a existência da via (do árabe, “o-caminho”). O troço em causa começa na Cruz da Légua (4 m.p. a Santarém), onde há vestígios romanos (Cirne) e segue pela antiga Ilha de Alvisquer até Azinhaga (Figura 2).

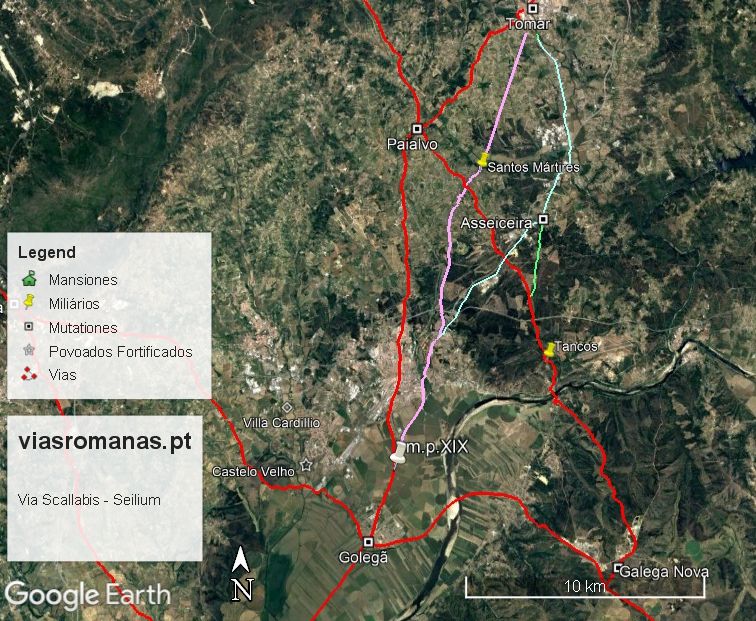

Cruzava depois o Rio Almonda em direcção à Golegã, mas a partir daqui as dúvidas acentuam-se, dado que não foi ainda possível determinar o local onde se fazia a travessia da Ribeira de Beselga. Existem várias possibilidades que reduzimos a três hipóteses. A primeira hipótese seguia mais a ocidente por Paialvo, trajecto mais de acordo com a viação antiga pois cruza a Ribeira da Beselga mais a montante . A segunda hipótese (cor rosa) seguia um percurso mais recto a Tomar cruzando a Ribeira de Beselga junto do miliário dos Santos Mártires. Por fim, existe ainda a hipótese da via seguir o percurso da antiga “Estrada Real” Santarém-Tomar passando em Atalaia e Asseiceira e Santa Cita, seguindo depois a margem direita do Nabão até Tomar.

Na Carta de Doação da albergariam de Saiceira em 1222 a Pedro Ferreiro e a Maria Vasques, sua mulher, com a “condição de a aproveitarem e utilizarem melhor do que os seus antecessores”, refere como limite oeste da propriedade a ‘strata colimbriana ad Sanctarem’ desde a “Conchada de Beselga” até ao término ‘inter ambas lagonas´ (PMM doc 72), no entanto, a localização destes locais é incerta e não sabemos a qual das hipóteses se refere.

Em síntese, a via de Santarém a Tomar seguia uma rota paralela ao rio Tejo até à Golegã, mas a partir daqui parece bifurcar, um ramo seguindo mais a oeste por Paialvo, Fungalvaz, Ansião e Eira Velha, em direcção a Coimbra, e outro, o referido no Itinerário, seguia directo a Tomar para aí cruzar o rio Nabão, continuando por Ceras rumo a Conímbriga. No entanto, não há acerto com as distâncias indicadas no documento para a etapa seguinte entre Seilium e Conimbriga, pois o Itinerário indica 34 milhas, valor manifestamente insuficiente para cumprir o percurso entre Tomar e Conímbriga, problema que será abordado na Parte 3 desta série de artigos, a propósito da localização de Seilium.