The recent proliferation of the so called “Camino de Santiago” (St. James’ Way), although it has its merits, is creating a distorted vision of the ancient road system by tracing indiscriminate routes all over the country without a secure historical basis. Some care in the elaboration of these routes is thus required in order to reflect the true reality of the ancient paths, instead of trying to “force” a route that is hovering here and there, vaguely in the direction of Santiago, and that in most cases has nothing to do with the ancient roads that served this pillgrimage.

Of course, one can start from any geographical point and go to Santiago, but that does not mean that the path was used for that purpose. The route used by the pilgrims would certainly be the ancient routes inherited from the Roman period (but in reality with much older origins…), and apart from a few minor variations introduced over time, these routes remained practically unchanged until the 19th century, when it was necessary to build a new road network better adapted to motorised traffic.

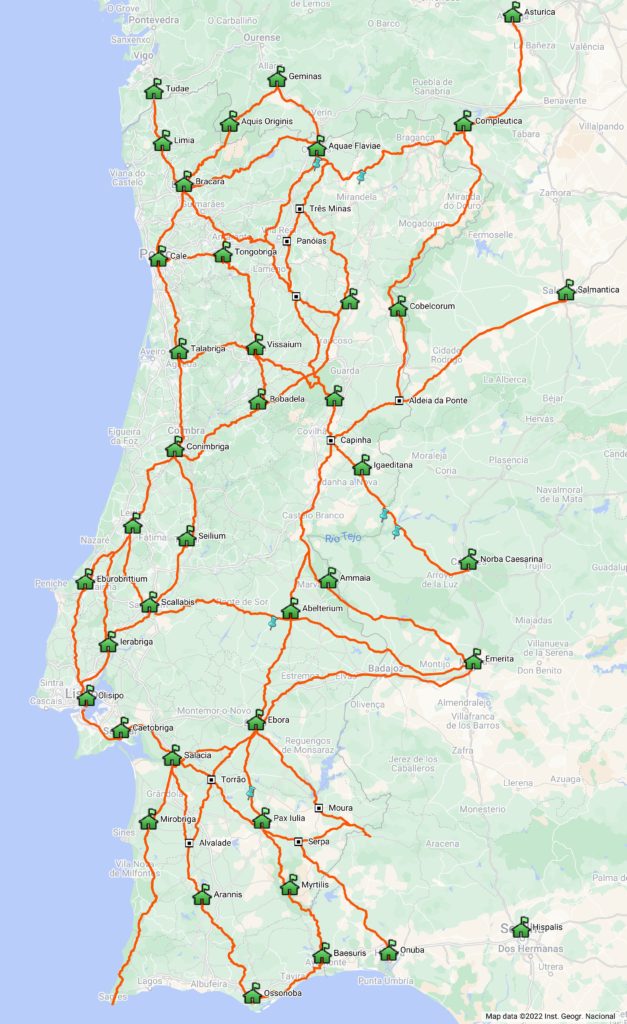

Now, for those departing from the current Portuguese territory, the two main access gates to Santiago would be Tui and Chaves. The first corresponds to the great S-N route from Lisbon which, like today, runs parallel to the coast passing through Santarém, Tomar, Coimbra and Porto, and then continues along the so-called “Central Way” via Barcelos to Valença. Naturally, for those coming from the Beiras region, the most direct route would be via Braga, continuing along the Bracara-Tudae road to Valença. This route aggregated various routes that crossed the River Douro respectively in Porto Antigo, Caldas de Aregos and Régua. From this last place, a route to Chaves run through the Sanctuary of Panóias and reached Chaves by crossing the heights of the Padrela Mountain, where it received another route also coming from another important crossing of the Douro River in Numão (Vesuvio/Ns. da Ribeira) that came through Carlão and Alto do Pópulo until it joined the Régua-Chaves axis near the important Roman mining exploitation of Trêsminas. From Chaves, the pilgrims would enter Galicia, heading towards Torre de Sandiás (Ourense), the station of Geminas mentioned in the XVIII Itinerary from Bracara to Asturica, an axis which crossed at this point, continuing from here to Santiago.

The prevalence of these ancient routes throughout the Middle Ages and even in much later periods makes it impossible to imagine that the route followed a “medieval route” to Santiago different from the one used in the Roman period, although here and there some variants have been introduced over the centuries. In this way, the map we present ends up being a panorama of the routes available for those who were heading to Santiago, which from any point quickly entered this ancient network of roads that practically covered whole the current Portuguese territory.

The result is that although we are talking about different periods in time, the Roman and medieval roads are essentially the same physical reality. This can be seen as we travel along these roads because the great majority of the shrines, hermitages, crosses and landstones of the medieval period marking the passage of the way are positioned in accordance with the Roman mile of about 1500 m. In other words, even on the stretches where there are no milestones, it is possible to follow this marking every thousand steps which accompany the pilgrim along the route.

The historical density and typology of these routes has nothing to do with this multiplicity of routes that have been created towards Santiago, distorting the historical reality, taking the pilgrim away from the true immersive experience that these historical routes provide.

February 2023